Modern DoS/DDoS: When “Traffic Flooding” Is No Longer the Only Threat

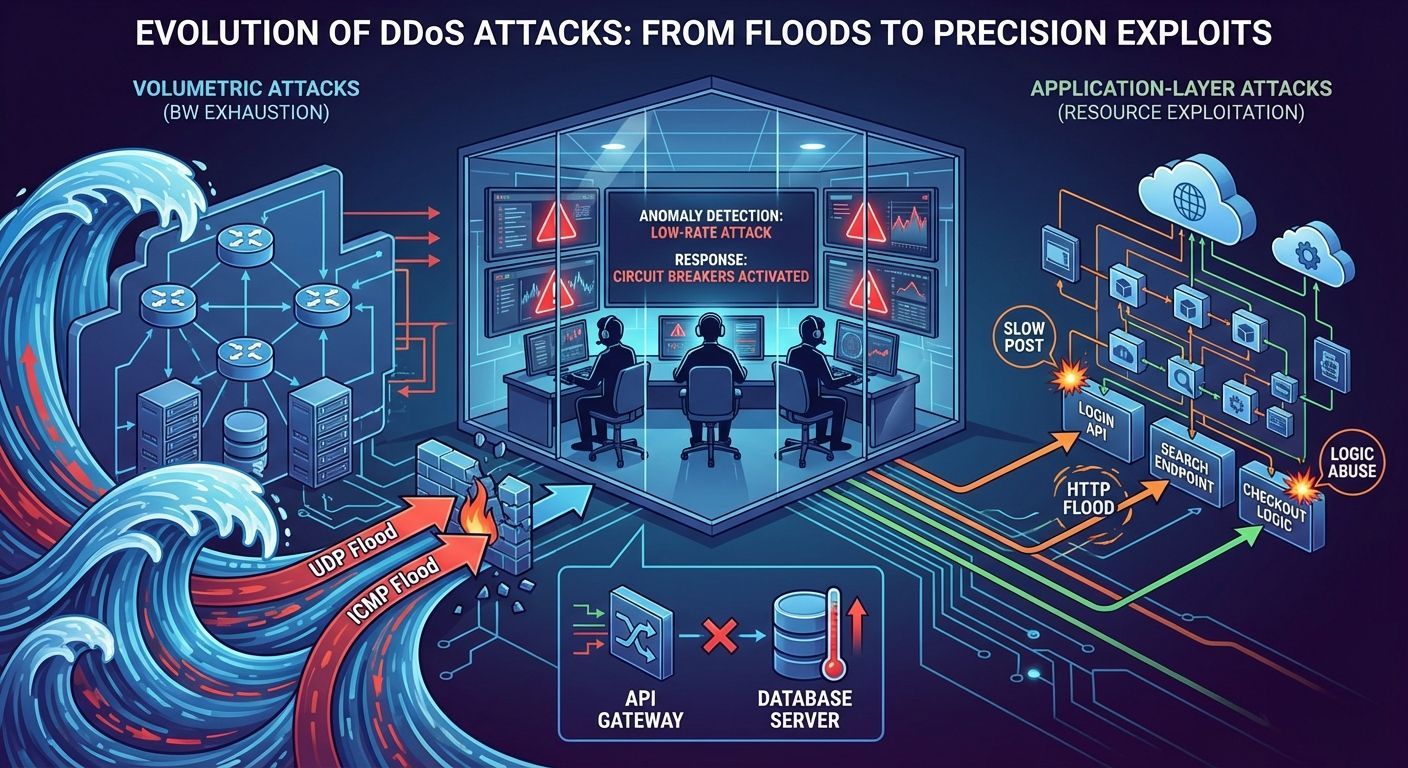

Remember the early days of the internet, when DDoS attacks were synonymous with overwhelming servers until bandwidth was exhausted? Back then, it was simple: whoever had the biggest botnet won. But the reality today is very different.

I've noticed that many engineering teams are still stuck in the old mindset—thinking DoS is always about "maximum traffic." In fact, the most damaging attacks can come from traffic that doesn't even look suspicious on the monitoring dashboard , but instead hits the weak points of our applications.

Let's talk about the realities of DoS/DDoS in 2025—from attacks that drain CPU with a single request to abuses of business logic that don't even look like "attacks" at all.

Why Large Bandwidth Is No Longer a Guarantee of Effective Attacks

In the past, the logic was simple: the more traffic sent, the faster the server would crash. But years of experience dealing with incidents show a different pattern.

I once handled a case where a server with 10 Gbps bandwidth could be brought down with less than 100 Mbps of traffic. How? Because every incoming request triggered a database operation that took 3-5 seconds to complete. It doesn't take much—just a few hundred requests per second can fill the connection pool and crash the application.

Here's what often gets overlooked: many downtime incidents are not due to a full "internet pipe," but rather because:

Internal resources run out first. Thread pools are exhausted because connections are held for too long. CPUs burn out because a single request triggers complex XML or regex parsing. Databases are overwhelmed because heavy queries are executed thousands of times. Email queues explode because password reset endpoints are abused. Or, more subtly, business logic is forced to run "expensive" operations over and over again until the system can't handle it.

This experience changed the way I view DoS. Now, when designing a system, the question I ask is no longer "how much bandwidth do we have?" but "which resources are most vulnerable to being depleted in an attack?"

Understanding the Attack Spectrum: Not Just Flooding

To make the discussion more practical, I usually divide DoS attacks into several categories based on "what is attacked" and "which bottleneck is forced to break."

Volumetric flooding is still around and still a threat. This is a classic attack that consumes bandwidth up to Gbps or even Tbps. Fortunately, mitigation is relatively advanced if we use a good CDN or Anycast.

Protocol attacks exploit vulnerabilities in the transport layer—SYN floods are still a favorite way to exhaust firewall state tables or load balancers. This is sometimes combined with other vectors for maximum effect.

Application layer attacks are the trickiest. A seemingly "normal" HTTP flood can shut down an application if each request is expensive. I've seen attacks with only 200 requests per second—very small by volumetric standards—but each request hit an uncached search endpoint and brought the application to its knees.

Slow DoS, or low-and-slow attacks, work by holding connections for as long as possible. The attacker doesn't send large amounts of traffic, but instead forces the server to wait and wait until all worker threads are used. Slowloris and Slow POST are still effective today, especially on poorly configured servers.

Resource exhaustion is my favorite topic to discuss because it's often overlooked. It's about triggering very demanding operations—parsing giant payloads, recursive regex queries, compression bombs. A single request can "lock up" the CPU or memory for an extended period.

Application logic abuse is the most subtle. It's not a technical bug, but rather an unconstrained exploitation of business design. Password reset floods, search abuse, endless add-to-cart attacks—these all seem like "normal" use cases, but they can cripple a system if implemented at scale.

Landscape 2025: Increasingly Scalable, More Complex Combinations

If you ask yourself, "What will change in 2025?" the answer isn't "a revolutionary new type of attack will emerge." What will change is scale and complexity.

Volumetric records continue to be broken. Tbps attacks, once considered fantastical, are now occurring multiple times. But what's even more disconcerting is the increasingly common trend of multi-vector campaigns .

From the various reports I've read and my firsthand experience handling incidents, a consistent pattern emerges: modern attacks rarely focus on a single vector. They combine volumetric attacks to distract operations teams, while covertly executing L7 attacks targeting critical API endpoints. Sometimes, there's also a probing phase to find vulnerabilities before a major attack begins.

It's no longer about "type of attack A or B," but "how do they combine A, B, C together to maximize impact and minimize the effectiveness of our mitigation."

Why Multi-Vector Makes Defenders the Most Difficult

From the perspective of someone who has sat in a war room during a major attack, I can say this: multi-vector attacks are a defender's nightmare.

Why? Because we're forced to defend against multiple layers at once—network, transport, application, logic—with limited resources and time. While the network team was busy mitigating volumetric issues, the application suddenly started slowing down due to an L7 attack. Once the L7 attack was resolved, it turned out there was a slow POST that had already exhausted the connection pool.

The complexity stems from several factors. First, the combination of vectors forces us to split resources. Second, attackers can adapt quickly—if one vector is blocked, they shift to another. Third, at the application layer, they can mimic normal traffic, making filtering more difficult without the risk of false positives.

Operationally, multi-vector forces us to make quick decisions in chaotic situations: when to aggressively block (risking blocking legitimate users) and when to maintain availability at the risk of slowing down the system. There's no "right" answer—everything is a trade-off.

This is why organizations serious about availability often don't settle for a single layer of defense. They combine edge protection (Anycast, CDN, scrubbing center), application protection (WAF, API gateway with intelligent rate limiting), and backend controls (circuit breakers, resource budgets, graceful degradation).

Campaign Patterns to Watch Out For

After analyzing various incidents, I noticed a recurring pattern in major DDoS campaigns:

It usually starts with initial probing —a small amount of traffic to map the system's response and look for vulnerabilities. Many teams skip this phase because the traffic isn't suspicious.

Then, it escalates to a multi-vector attack , combining several vectors simultaneously. This is the most intense phase.

Interestingly, many modern attacks are short but brutal —perhaps only 5-10 minutes, but with extreme intensity. This contrasts with older attacks that could last for hours.

Some cases have an element of ransom or extortion — the attacker sends a message "pay or we'll continue."

And almost all of them use amplification and evasion techniques for efficiency and to avoid signature-based detection.

Why is this pattern important to understand? Because defenses that simply "look for spikes" or "wait for the alert threshold to be exceeded" are often too late. If we can detect the probing phase, we have more time to prepare. This is why behavioral analytics and anomaly detection are increasingly important—they can catch abnormal patterns before they become full-blown attacks.

API Endpoints: A Favorite Target That's Often Overlooked

Let's be honest: modern applications are API-first. Even a seemingly simple website may contain dozens of API endpoints for authentication, search, content delivery, payment integration, and so on.

And this is what makes APIs a favorite target: the attack efficiency is very high . With a small bandwidth, attackers can have a big impact because APIs connect directly to the backend and database.

I often see some classic problems:

Many endpoints are publicly exposed without adequate protection. There are "expensive" operations—complex queries, large data aggregations, report rendering, PDF exports—that anyone can invoke. Rate limiting is often only implemented at the edge, while internal APIs remain vulnerable. And for CMSs, many use default REST APIs with predictable endpoints.

A real-life example I've handled: an e-commerce site had an uncached search endpoint with no internal rate limits. The attacker simply sent a variety of search queries at 500 requests per second—not much considering their traffic—but the database immediately spiked because each query hit a large table without proper indexes. The site went down within 3 minutes.

Headless Architecture: Flexible, But Increases Attack Surface

A headless or API-first architecture offers incredible flexibility—the CMS becomes a pure backend, the frontend can be multi-platform, and the API acts as a bridge. This is powerful, but it also means a wider attack surface.

In this model, if an API goes wrong, the impact is immediately cascading: API overload → frontend fails to render → users see an error or blank page. Database spikes due to "expensive" endpoints → all database-dependent services are affected. Downstream integrations (email queues, payment gateways, CRMs) can also be affected.

My experience designing headless systems has taught me one thing: mitigation can't just be "install a CDN" or "use a WAF." We need to design the blast radius well. If one endpoint goes down, it shouldn't bring down the entire system.

This means proper service isolation, circuit breakers for each dependency, an aggressive cache layer, and graceful degradation. If the search endpoint goes down, users can still browse and checkout—the search may be temporarily disabled or served from a stale cache, but the application won't crash completely.

Mitigation Strategies for the Era of Low-Rate and Logic Abuse

For volumetric attacks, frankly, the technology is mature. Large CDNs and scrubbing centers can handle Tbps of traffic. But the challenge now lies in intelligent, low-rate attacks —those that exploit the payload or application logic.

The solution I've seen that works is a combination of several layers:

A WAF with deep inspection that can recognize destructive payload patterns, not just signature matching. Anomaly detection and behavioral analytics to catch deviations from the normal baseline—this is crucial for detecting attacks that mimic user behavior. Autonomous defense that can respond quickly without manual intervention—useful for short-duration burst attacks. Aggressive CDN caching to reduce the load on the origin. And Anycast to diffuse traffic and buy time for mitigation.

But technology is only half the story. What distinguishes "resilient" organizations is their layered control design and operational discipline.

A Practical Checklist That Can Be Applied Immediately

From my experience building and maintaining production systems, this is the checklist I find most actionable:

At the edge layer (CDN/WAF/API gateway), implement identity-based rate limiting—API keys, user tokens, sessions—not just IP. IP-based rate limiting is easily bypassed by botnets. Install bot management with adaptive challenges to filter non-human traffic. And create special rules for expensive endpoints: search, login, password reset, data export.

At the application layer , use aggressive caching for popular queries, especially read-heavy ones. Implement circuit breakers for all external dependencies—don't let one service go down. Set timeouts and budgets per request: the maximum CPU time, database time, and memory allowed. Limit concurrency for heavy endpoints with queueing and backpressure mechanisms.

In the data layer , enforce query budgets—every public query must use an index. Default pagination and hard limits for parameters like limit, offset, and complex filters. Protect against "query fan-out" or N+1 problems on public endpoints.

In the observability layer , don't just monitor volume—monitor p95/p99 latency, error rate, and saturation metrics (CPU, memory, thread pool). Alerts are based on behavior changes, not just static thresholds. And most importantly, have a clear mitigation runbook. "When a search endpoint is attacked, do the following: throttle aggressively, serve from cache, degrade features gracefully, notify the team."

Parser Bomb: A Small Attack That "Explodes" Resources

In the resource exhaustion category, there is a particularly interesting type of attack because it demonstrates a fundamental principle: a small payload can force a parser to do exponential work .

XML bombs exploit entity expansion in DTDs to drastically inflate parsing results—a payload of a few KB can expand to GB in memory. JSON bombs typically use very deep nesting or structures that trigger high parsing costs.

I won't share an example payload here for safety reasons, but the point is: this attack proves that "request size" is not a reliable indicator of threat level.

How to Protect Yourself from Parser Bombs

An effective approach is preventative, not reactive. Don't wait for it to happen—make sure the parser has no room for uncontrolled expansion from the start.

Concrete steps that can be taken:

Disable DTDs and entity expansion in XML parsers, or if they must be enabled, set strict limits. Limit the maximum depth in JSON parsers—most legitimate use cases don't require nesting more than 5-10 levels. Validate input at the entry point: check payload size, structure, and schema before parsing. Ensure all parsers and libraries are up-to-date and audit their default configurations. Integrate with a WAF or monitoring system to detect anomalous patterns in payload structures.

Most importantly: awareness. Many developers don't realize that standard parsers have inherent vulnerabilities if not configured correctly. This is something that should be included in secure coding guidelines and code review checklists.

Availability Is a Design Result, Not Just Protection

After years of dealing with DDoS incidents and availability issues, one of the most profound lessons is this: availability isn't just an infrastructure or security issue—it's a product of good application design .

If our systems are only prepared for "traffic floods," we're still vulnerable to intelligent low-rate attacks. If APIs are the backbone of applications, they should be treated as critical assets: throttled with intelligent rate limits, monitored with meaningful metrics, and provided with design guardrails like timeouts, circuit breakers, and resource budgets.

As multi-vector threats become more common, defenses must also be multi-layered: edge protection, application-level control, data layer safeguards, and operational readiness. There's no silver bullet—it's a combination of technology, design, and team discipline.

And perhaps most often forgotten: defense is an ongoing process . Attacks evolve, our applications change, traffic patterns shift. What's effective today may not be sufficient tomorrow. This is why monitoring, learning from incidents, and continuous improvement are fundamental to maintaining availability.

At the end of the day, users don't care whether we're hit by a Tbps attack or "just" a slow POST. All they know is that the site is inaccessible. And that's what we must avoid at all costs.